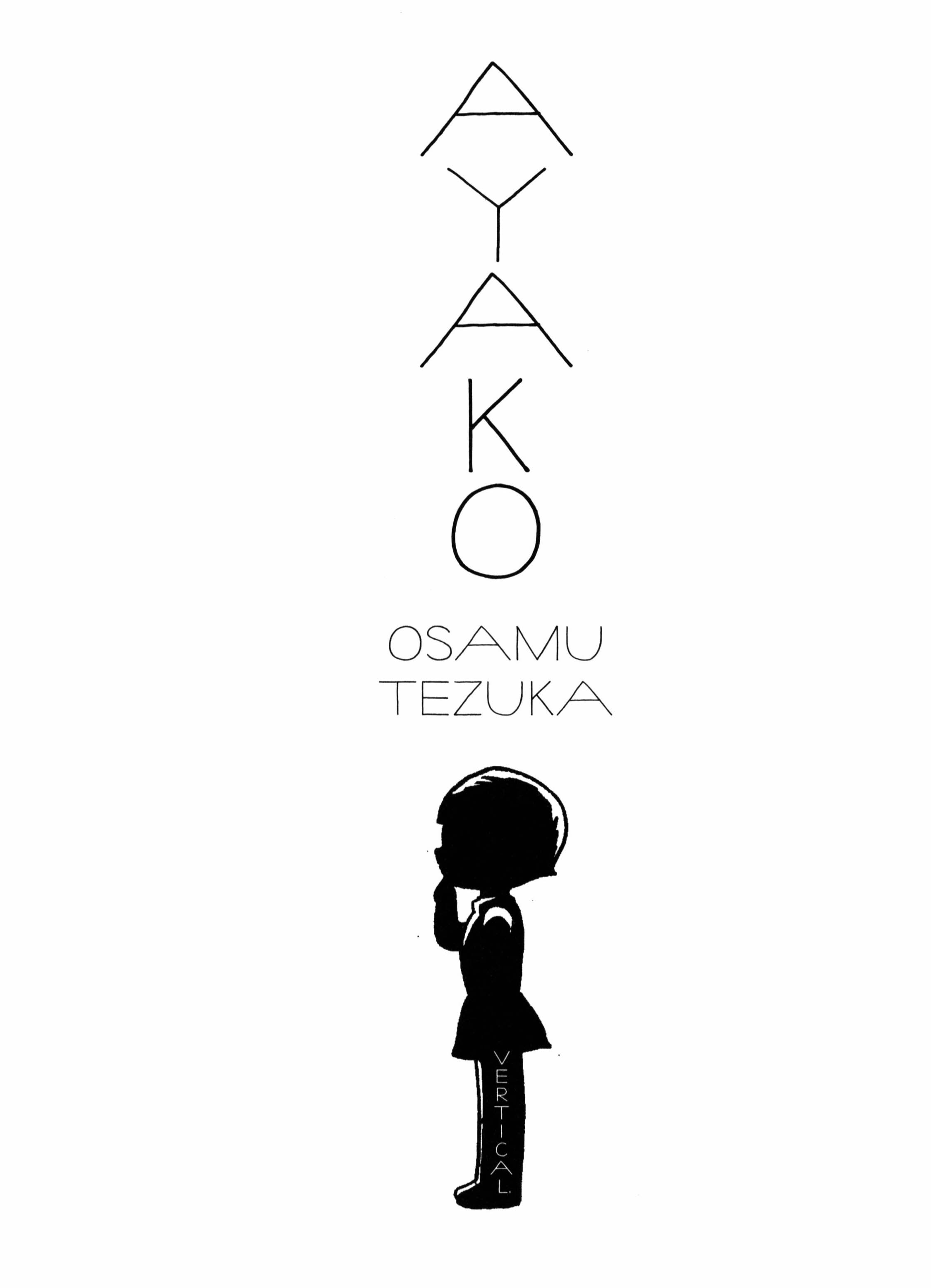

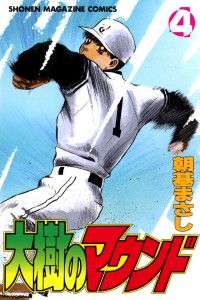

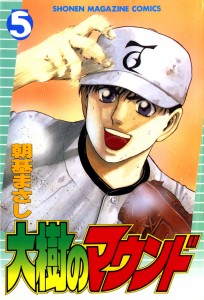

I’m still on a baseball manga kick and I still have a lot of ground to cover. I’ve read some good stuff, some not so good stuff and just recently I read Daiju no Mound (大樹のマウンド) by Masashi Asaki, which is flat out terrible. Unlike something like A Single Match, which is terrible because it makes no sense, or Ayako, which is bad because it’s so trashy, Daiju no Mound is bad because the author doesn’t know the first thing about writing likable characters. Since there are no summaries out there, I’ll have to write one myself this time. Tch.

Daiju no Mound is about a boy in junior high named Daiju. He badly wants to play baseball. However his dad, who pitched at Koshien but ruined his shoulder after going pro and never made it out of the minors, is dead set against Daiju following in his footsteps. In his third year of junior high, however, Daiju runs into the cute manager of a little league team who wants Daiju as their ace pitcher and won’t take no for an answer. Will Daiju be able to run from his destiny?

Of course not. Otherwise the manga would have ended, mercifully enough, after two chapters instead of five volumes. Daiju himself is bland but occasionally stubborn with a weakness for pretty girls, like most shounen heroes. If he was the only character in Daiju no Mound we wouldn’t have a problem. Unfortunately everyone around him just sucks. I’m not going to cover every single character in the series, firstly because this manga doesn’t deserve that kind of coverage and secondly because I have luckily started to forget them all. The worst culprits, who made the manga nigh unreadable, are:

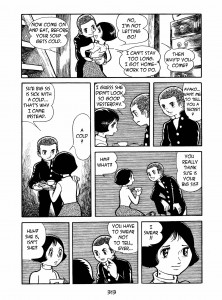

The cute manager, whose name I’ve forgotten: Her sole raison d’existence is to nag, nag, nag, nag, nag, nag x200 Daiju into doing things he usually doesn’t want to do. He had made peace with not being able to play baseball, for example, but she just wouldn’t let it drop. She showed up at his house day after day after day until he joined the little league team.

The cute manager, whose name I’ve forgotten: Her sole raison d’existence is to nag, nag, nag, nag, nag, nag x200 Daiju into doing things he usually doesn’t want to do. He had made peace with not being able to play baseball, for example, but she just wouldn’t let it drop. She showed up at his house day after day after day until he joined the little league team.

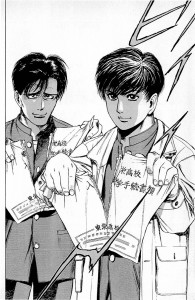

That was bad enough. But then once it was time to pick high schools, she ignored the school he was planning to go for and dragged him to another high school and nagged, nagged, nagged him – with the help of his team mates – until he finally gave in and went to that school.

Sure it’s his fault for not having the will to stand up to this annoying girl, but she doesn’t make her case easier by being such a noisy, nagging shrew. The author quickly realized what a pain she was and tried to give her some sob story about “Boo hoo, I have a weak heart, my parents don’t want me to be a manager but I love baseball so much, boo hoo” but it only makes her even more irritating, so that plotline is quickly dropped.

The little league coach: I can’t remember his name either, so I’ll call him Coach. It turns out Coach also led Daiju’s dad to Koshien. If that’s the case then he should be aware of the disaster that later befell Daiju’s dad and thus more likely to protect young pitcher’s arms, right? Wrong! Instead Coach goes on and on about finding a pitcher who can be the future of Japanese baseball, but when he finds him what does he do? He promptly begins to destroy Daiju’s shoulder!

Coach is so focused on winning some little league tournament (which they lose quickly anyway) that he rushes Daiju into playing in the tournament without teaching him a thing about proper pitching technique, without imposing pitch limits, without teaching him anything about protecting himself, nothing.

And when Daiju does come down with a shoulder injury, predictably enough, you would expect Coach to bench him and tell him to take better care of himself, right? Wrong! Instead he follows Daiju from doctor to doctor until they find a quack that okays him playing, then Coach teaches Daiju another pitch he can use while his very badly injured shoulder is healing.

When Daiju finished middle school and moved to the high school level, I thought “At last, he’s going to be paired up with a sensible coach!” You know, someone who knows that protecting a future star means not destroying him in a petty tournament at age 15. But noooo, right after Daiju enrolls a coaching change is announced and here comes Coach again. Nooooo! I stopped reading at that point and jumped to the end. There was no point, really.

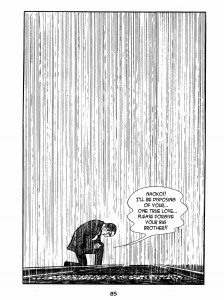

Daiju’s dad: Parenting is a tough job, no question about it, and being a single dad to a teenager must be even tougher. I want to cut Daiju’s dad some slack, but he made a lot of mistakes in handling Daiju. The first one was making baseball some kind of ‘forbidden fruit,’ which only made it more enticing to the kid. He’s a teenager, after all.

Mistake number two, which was even worse, was not guiding and advising Daiju once the kid inevitably started playing baseball. Daddy must have known first-hand all the pitfalls awaiting a young, highly gifted pitcher. In fact, that’s the very reason he didn’t want his son playing in the first place.

Once he gave tacit approval for Daiju to play, then, he should have done everything in his power to avoid a repeat of his own fate. Check his form, check his diet, check what kind of exercises he’s doing. Impose pitch limits and make him stick to them. Teach him warning signs that mean ‘Stop immediately.’ And when it comes to picking a high school, help him find a school with a baseball team that is active but not overly-rigorous. Basically just take an interest instead of throwing up your hands and walking away. You’re his dad, for goodness’ sake!

Once he gave tacit approval for Daiju to play, then, he should have done everything in his power to avoid a repeat of his own fate. Check his form, check his diet, check what kind of exercises he’s doing. Impose pitch limits and make him stick to them. Teach him warning signs that mean ‘Stop immediately.’ And when it comes to picking a high school, help him find a school with a baseball team that is active but not overly-rigorous. Basically just take an interest instead of throwing up your hands and walking away. You’re his dad, for goodness’ sake!

Anyway, the characters aside, the manga itself wasn’t remarkable in any way. The art was pretty good (albeit heavily inspired by Hajime no Ippo) and the action was usually easy to follow, but apart from that there’s nothing to recommend Daiju no Mound for. Except, I guess, that it made Masashi Asaki realize that he can draw but he can’t write. Since then he’s made his living as an artist partnering writers like Ira Ishida and Yuma Ando, so you may have seen his work in titles like Shibatora and Psychometrer Eiji.

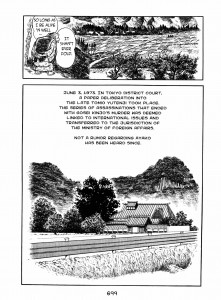

Since the manga was so bad I’m not going to bother doing a sample chapter. The chapters in this manga are about 70 pages long anyway, so the odds were against it from the start. Most likely I’m not going to do samples of future series either (too much trouble, also it’s illegal) so I’ll spoil the abrupt ending: Daiju’s high school team plays some other team in the Koshien qualifiers and win. They’re probably going to Koshien, but the manga was cancelled just then so we’ll never know how they fared when they got there. The end.