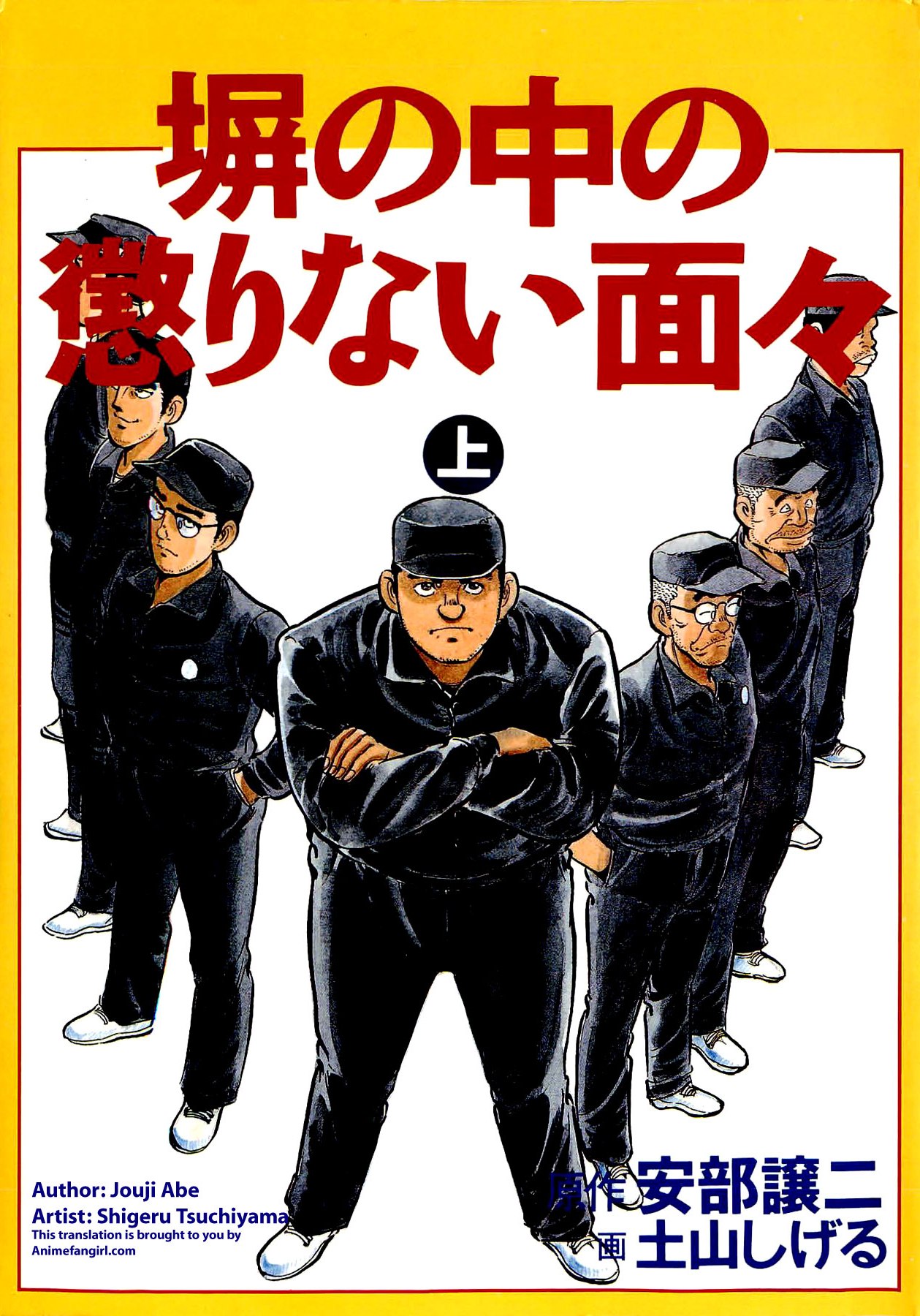

It’s been a while since I read something I actually enjoyed. Doing Time by Kazuichi Hanawa is quite similar to Hei no Naka no Korinai Menmen which I mentioned a few weeks ago, in that it’s a short chronicle of the author’s time spent behind bars. Both titles take a slice of life approach to the subject, showing what happens day in and day out. Who they meet, what they do, what they wear, where they sleep, and so on and so forth. If you read closely you’ll even see Hei no Naka referred to in Doing Time afterward, translated as “Some guys never learn behind bars.”

The similarities are many, but the difference in tone is astounding. Hei no Naka no Korinai Menmen has a puffed up, self-righteous moralizing tone to it while Doing Time largely steers clear of discussions of right and wrong and just focuses on everyday life. Furthermore, since Doing Time is originally a manga, written and drawn by the actual prisoner, while Hei no Naka is a manga adaptation of a novel, Doing Time has a livelier, more vivid and more realistic feel to the art and the details of life.

Comparing the two series would be an interesting exercise, seeing as there aren’t that many autobiographical titles set in prison. It would be an interesting exercise for someone else to do, but today I’m just here to talk about Doing Time. As usual, the summary:

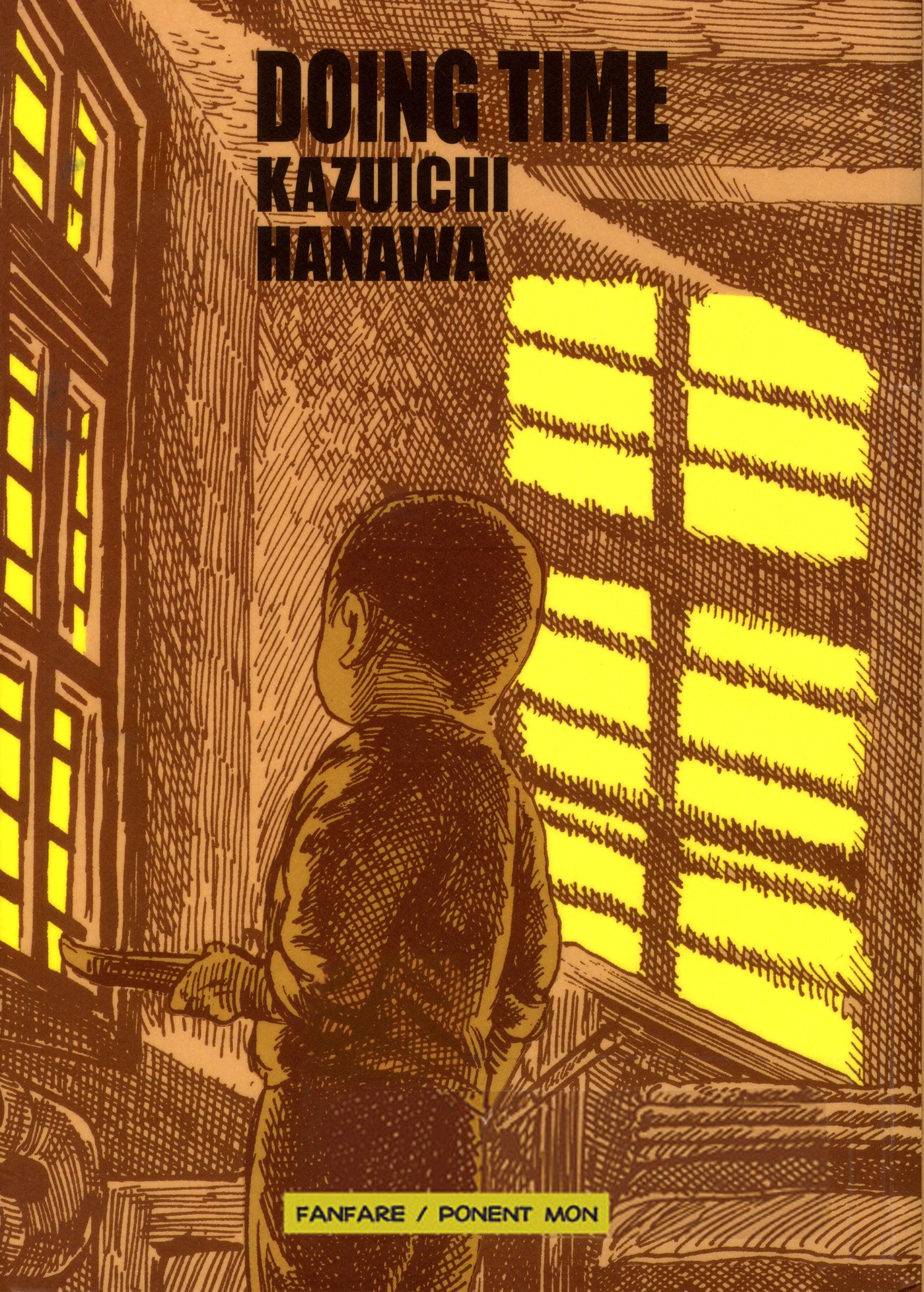

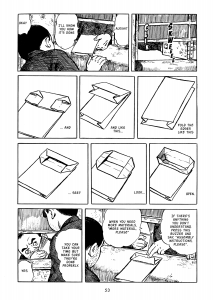

Summary 1: Up to now, Kazuichi Hanawa expressed himself through works of fiction. The fantastic world of tales from the Middle Ages in Japan was his favorite setting. In 1994 Hanawa was arrested for owning a firearm. An avid collector of guns, he was caught whilst testing a remodeled handgun in the backwoods, miles away from anyone, and imprisoned for three years. Forbidden to record any details whilst incarcerated, Hanawa recreated his time inside after his release. He did so with a meticulousness rarely found in comics as every detail of his cell, every meal that was served, the daily habits of his cell-mates and, above all, the rigid regime are minutely noted and bring us into the very mindset of a Japanese prisoner. Made into a live action movie in 2002 by Sai Yoichi (All Under the Moon).

Summary 1: Up to now, Kazuichi Hanawa expressed himself through works of fiction. The fantastic world of tales from the Middle Ages in Japan was his favorite setting. In 1994 Hanawa was arrested for owning a firearm. An avid collector of guns, he was caught whilst testing a remodeled handgun in the backwoods, miles away from anyone, and imprisoned for three years. Forbidden to record any details whilst incarcerated, Hanawa recreated his time inside after his release. He did so with a meticulousness rarely found in comics as every detail of his cell, every meal that was served, the daily habits of his cell-mates and, above all, the rigid regime are minutely noted and bring us into the very mindset of a Japanese prisoner. Made into a live action movie in 2002 by Sai Yoichi (All Under the Moon).

Most reviews will note how resigned to his lot and almost content the main character seems, and they’re right. Apart from the first chapter that deals with his nicotine cravings and the chapter about his annoyance at having to yell “Pleeease!” when he wants anything from the guards, his view of prison life seems remarkably positive. He and the other prisoners even look forward with great excitement to certain simple pleasures, like getting a special bread once a month or their New Year’s meal.

But when you think about it, there’s no reason why Hanawa shouldn’t be content. The Japanese prison he describes seems like a veritable paradise compared to what I know of prisons in other cultures. Your average prisoner in, say, Mali or Bolivia would kill to share a comfy, disease-free cell with only four other people. They get three healthy meals a day, they have running water, their cells are huge and spacious, their cell toilet even has a privacy screen, etc. Heck, lots of people on the outside even in Japan would be glad to have digs like that.

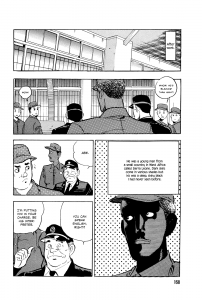

Not only that, but they also have all kinds of privileges that one wouldn’t expect prisoners to get. For example some prisoners have personal shavers. The prisoners also keep bottles (unclear if they’re glass or plastic) of sauce in their cell, surely a potential weapon if there ever was one. They’re even allowed to watch TV – not a TV in a general room but TVs right in their own cells, plus they have access to tons of books and all the latest magazines, as long as they’re considered ‘educational.’

And you might think, well that must be a minimum-security prison for people who haven’t done anything too serious, right? That’s what I thought at first, but later on the story introduces armed robbers and cold-blooded murderers, casually and unrepentantly chatting about their crimes and looking forward to their New Years’ treats just like everybody else. As the author wryly comments on one page, prison is so nice there’s no incentive to go straight!

In a sense, reading Doing Time is a good way to get a sense of Japanese culture as a whole. You learn a lot from the needless bureacracy, the tightly regimented lifestyles (even right down to when to walk, when to trot, when to look out the window and when not to) and the relative freedom and comfort the prisoners enjoy. It’s something only a country with a relatively low rate of violent crime (even taking into account the thousands of crimes the Japanese police hide every year) can get away with. It might be an interesting read for the Japanophile just for that alone.

For everyone else, Doing Time is still a good read, being a rare non-dreary, non-preachy tale of prison slice-of-life. You’ll come away feeling quite upbeat and cheerful, and more than a little hungry after pages upon pages of delicious-looking prison food. It’s been a while since I reviewed something I recommend and would be happy to re-read, but I think most people would have a good time, aha, with Doing Time.